Back to > Major Fruits | Minor Fruits | Underutilized Fruits

![]()

|

||

|

|

||

Pest and Disease Management:

Weeds: Most growers use only mechanical cultivation and hand-hoeing for weed control in the growing regions. Herbicides are applied with shallow incorporation, and transplants are placed with the roots below the treated zone. Postemergence herbicides are used to control grasses. Metam sodium is used for preplant weed suppression. Plastic mulch provides excellent weed control over the plant row. The inter-row space can be kept clean by using a registered knockdown herbicide. Where crops are grown without plastic mulch, grass control is obtained by applying registered post emergence herbicides (It is important to read the chemical label, melons are very susceptible to herbicide damage especially when the plants are small). Mechanical methods will give good control and are most effective if the vines are “tucked in” before cultivation. Cultivation between rows should be shallow to avoid injury to the root system.

Insect pests of watermelon: A number of insect species including caterpillars, mites and thrips can cause damage to the plants but are readily controlled using registered insecticides. Aphids can be very damaging as they are the vector for mosaic viruses.

| Scientific Name | Common Name | Damage | Control |

| Aphis gossypii | Melon or Cotton Aphid | Sucks sap and weakens plant.Leaves curl, shrivel and may turn brown and die Secretion of ‘honeydew’ causes sootymould to develop. | Biological – use of ladybird beetle Chemical – Fastac Decis, karate (1.5ml/ L water) or Sevin 85 wp (1.5g/ L) |

| Diaphania hyalinata | Pickleworm or melon worm | Caterpillars feed on leaves and flowers. Sometimes they bore into the developing fruit. | Use of appropriate contact insecticide such as malathion (2 ml/l of water) |

| Diabrotica seporata | Leaf cutting beetle | Developing seedlings are affected by adults Leaves become (2 ml/l of water) skeletonized. | Use of appropriate contact insecticide such as malathion |

| Thrips palni | Thrips | Sucks sap of leaves which become scorched. Infestation or most severe during sunny weather | 1. Crop rotation 2. Chemical –Regent (10- 30 ml/L water), Vydate L (2.5 ml/ L water) or Admire |

| Bemisia tabaci | White fly | Sucks plant sap, leaves become chlorotic and are shedded prematurely | Cultural – keep farm free of weeds Chemical – Use soap based products or other chemicals such as Pegasus or Vydate l at the recommended rates. |

| Liriomyza sp. | Leaf miner | Larva feeds between leaf surfaces resulting in ‘chinese writing” | Chemical control – using Trigaul, Admire, Pilarking, Vertimex, Abamectin and Newmectin at the recommended rates. |

Disease Management:

Diseases that affect watermelons are similar to those of pumpkins. Diseases can cause extensive damage to crops. The following are some common diseases of watermelon:

| Disease | Symptom | Management |

| Bacterial fruit blotch | Oval water-soaked areas on fruit crop | *Registered seed treatment, hygiene, *registered copper-based sprays |

| Fusarium wilt | Yellowing, wilting, stunting | Rotation and resistant varieties |

| Gummy stem blight | Brown spots on leaves; reddish ooze from runners; black sunken spots on fruit | *Registered fungicides and crop hygiene |

| Mosaic viruses (CMV, PRSV-W, WMV, ZYMV) | Mosaic pattern on leaf, leaf and fruit distortion | Deter aphids, crop hygiene |

| Powdery mildew | Greyish patches on older leaves | *Registered fungicides or resistant strains |

| Damping off Root-knot nematodesSudden death | Rotting and death of seedlings Wilting and stunted growthRapid wilting Rotting roots | Good soil drainage Soil treatmentImprove drainage control irrigation crop rotation. |

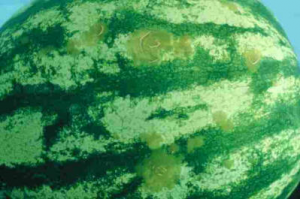

Advanced stage of lesion development of bacterial fruit blotch of watermelon |

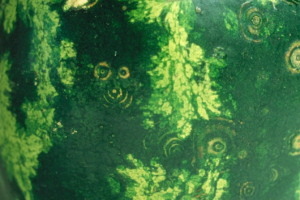

Leaf symptoms of bacterial fruit blotch |

Vertebrates: Mice can cause major problems in melon crops prior to emergence; they will dig out and eat large quantities of seed. The crops may have to be replanted several times, resulting in delayed harvests. Pre-germinating seed or planting container grown seedlings will reduce loss.

Crows can be a devastating and annoying pest. Just before harvest they can reduce the salability of melons by punching holes through the skin with their sharp beaks. Often not content with eating from just one melon, the crow will hop from melon to melon, in this way populations of crows can wipe out an entire crop in just a few days. Crows can be deterred with the use of a sound device such as a gas gun, or bird alarm.

Fruit physiological disorders:

Physiological disorders are caused by nonpathogenic agents that affect fruit quality. Usually, aesthetic quality is degraded. The cause can be either one or a combination of environmental, genetic, or nutritional factors.

Blossom-end rot (BER) is caused by uneven irrigation that leads Ca-deficiency in the flower (blossom) end of the fruit. It is worse in hot, dry, windy conditions where moisture stress is more likely to occur. Symptoms include young fruit drop and brown rotting lesions at the blossom end of older fruit. Good water management and ensuring sufficient soil calcium availability will usually address the problem. Soil or irrigation water salinity may also promote blossom end rot.

Blossom-end rot results in dark-brown, sunken leathery lesion on the blossom-end of fruit.

Internal cracking is caused by cool temperatures during early fruit-filling period. Other influences are stop-start growth, excess nitrogen, low boron levels, or heavy infrequent watering at fruit fill. Affected melons tend to be flattened in shape and feel lighter than usual.

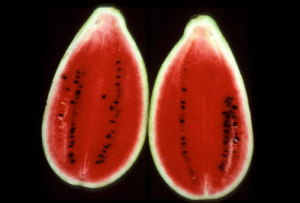

Hollow heart fruit is expressed as flesh separation |

Bottleneck is caused by poor pollination that results in constricted stem-end growth |

Sunburn can be a major problem in dark or darker striped melons. It is rarely seen in light colored melons. Sun burning can also occur in melons stacked in the field with their underside facing upward.

Cross stitch is the name given to this disorder by Dr. Don Maynard of the University of Florida. It is characterized by elliptical or oval lesions that tend to be positioned perpendicular to vascular bundles on watermelon rind (See picture below). The disorder occurs very infrequently. Cross stitch was observed in Indiana in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Attempts to isolate a pathogenic organism from affected tissue were not successful and confirmed initial suspicions that cross stitch is a non-infectious disorder

Spongy end occurs in poorly pollinated melons. These melons may turn yellow and drop off the vine early in their development or partly develop with the stylar end soft and spongy. This area is also slightly pointed. Internally, there is very poor seed development at the spongy end.

Reference:

- “An African Native of World Popularity.” Texas A&M University Aggie Horticulture website. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- Anioleka Seeds USA. “Yellow Crimson Watermelon”. http://www.vegetableseed.net/heirloom-vegetable-seeds/melon-seeds/watermelon-seeds/yellow.html. Retrieved on 2007-08-07.

- Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. “Watermelon Heirloom Seeds”. http://rareseeds.com/seeds/Watermelon. Retrieved on 2008-07-15.

- Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. “Carolina Cross Watermelon”. http://rareseeds.com/seeds/Watermelon/Carolina-Cross. Retrieved on 2008-07-15.

- (BBC) Square fruit stuns Japanese shoppers BBC News Friday, 15 June, 2001, 10:54 GMT 11:54 UK

- “Black Japanese watermelon sold at record price“. http://ap.google.com/article/ALeqM5jJBRT0pnOdQVMUzzkKC_cGHo7IdQD914F62O0. Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- Blomberg, Marina (June 10, 2004). “In Season: Savory Summer Fruits.” The Gainesville Sun. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- “Charles Fredric Andrus: Watermelon Breeder.” Cucurbit Breeding Horticultural Science. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- Collins JK, Wu G, Perkins-Veazie P, Spears K, Claypool PL, Baker RA, Clevidence BA. (2007). Watermelon consumption increases arginine plasma concentrations in adults. Nutrition 23(3):261-6.

- “Cream of Saskatchewan Watermelon“. http://www.seedsavers.org/prodinfo.asp?number=778. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- “Crop Production: Icebox Watermelons.” Washington State University Vancouver Research and Extension Unit website. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of Plants in the Old World, third edition (Oxford: University Press, 2000), p. 193.

- Dayer, R.D. (1975). The Genera of Southern African floweringbplants Vol. 1. Dicotyledons, Department of Agricultural Technical Services. South Africa: Botanical Research Institute.

- Evans, Lynette (2005-07-15). “Moon & Stars watermelon (Citrullus lanatus):Seed-spittin’ melons makin’ a comeback”. http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2005/07/16/HOG4UDNGDB1.DTL. Retrieved on 2007-07-06.

- Hamish, Robertson. “Citrullus lanatus (Watermelon, Tsamma).” Museums Online South Africa. Retrieved Mar. 15, 2005.

- H. Mandel, N. Levy, S. Izkovitch, S. H. Korman (2005). “Elevated plasma citrulline and arginine due to consumption of Citrullus vulgaris (watermelon)”. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 28 (4): 467–472. doi:10.1007/s10545-005-0467-1.

- “The column of watermelon peel from 5hpk.com”.

- http://www.5hpk.com/Html/TOPIC/200807172.html. Retrieved on 2008-07-15.

- http://www.agriculture.gov.gy/Farmers%20Manual/PDF/Watermelon.pdf. Retrieved on 2009-07-30

- Jian L, Lee AH, Binns CW. Tea and lycopene protect against prostate cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16 Suppl 1:453-7. 2007. PMID:17392149.

- Lucotti P, Setola E, Monti LD, Galluccio E, Costa S, Sandoli EP, Fermo I, Rabaiotti G,Gatti R, Piatti P. (2006). Beneficial effects of a long-term oral L-arginine treatment added to a hypocaloric diet and exercise training program in obese, insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab:291(5):E906-12.

- Matos HR, Di Mascio P, Medeiros MH. Protective effect of lycopene on lipid peroxidation and oxidative DNA damage in cell culture. Arch Biochem Biophys 2000 Nov 1;383(1):56-9 2000.

- “Melitopolski Watermelon“. http://www.seedsavers.org/prodinfo.asp?number=267. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- “Moon and Stars Watermelon Heirloom“. http://rareseeds.com/seeds/Watermelon/Moon-and-Stars. Retrieved on 2008-07-15.

- “Moon and Stars Watermelon“. http://www.seedsavers.org/prodinfo.asp?number=266. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- Motes, J.E.; Damicone, John; Roberts, Warren; Duthie, Jim; Edelson, Jonathan. “Watermelon Production.” Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- Müller T, Ulrich M, Ongania KH, Kräutler B. (2007). Colorless tetrapyrrolic chlorophyll catabolites found in ripening fruit are effective antioxidants. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(45):8699-702.

- National Research Council (2008-01-25). “Watermelon”. Lost Crops of Africa: Volume III: Fruits. Lost Crops of Africa. 3. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-10596-5. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=11879&page=165. Retrieved on 2008-07-17.

- “Oklahoma Declares Watermelon Its State Vegetable“. 2007-04-18. http://cbs4denver.com/watercooler/watercooler_story_108064706.html. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- “Orangeglo Watermelon“. http://www.seedsavers.org/prodinfo.asp?number=1108. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- Parsons, Jerry, Ph.D. (June 5, 2002). “Gardening Column: Watermelons.” Texas Cooperative Extension of the Texas A&M University System. Jul. 17, 2005.

- Salleh, H. (1986). Constrain and challenges in melon breeding in Peninsular Malaysia. Proc. Of the Plant and Animal Breeding Workshop, Serdang: MARDI

- Shosteck, Robert (1974). Flowers and Plants: An International Lexicon with Biographical Notes. Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co.: New York.

- Southern U.S. Cuisine: Judy’s Pickled Watermelon Rind

- http://home.howstuffworks.com/watermelon3.htm

- Stone, B.C. (1970). The flora of Guam. Micronesic 6: 562.

- Vegetable Research & Extension Center – Icebox Watermelons”. http://agsyst.wsu.edu/Watermelon.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-02.

- Wada, M. (1930). “Über Citrullin, eine neue Aminosäure im Presssaft der 28. Wassermelone, Citrullus vulgaris Schrad.”. Biochem. Zeit. 224: 420.

- “Watermelon.” The George Mateljan Foundation for The World’s Healthiest Foods. Retrieved Jul. 28, 2005.

- “Watermelon History.” National Watermelon Promotion Board website. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.